I had no intention of making a film about journalists in Mexico. I began this project as an examination of how an overlooked part of the U.S.-Mexico border — the region encompassing the twin cities of Calexico and Mexicali — was changing, in some quiet and not-so-quiet ways. The area is both physically beautiful and contradictory. It is both a desert and one of the most productive farming regions in North America. It is also considered by some to be a major staging ground for drug trafficking into the United States.

Though I was born in Mexico, I had no personal connection to this stretch of the border. Instead, I became interested in the area in 2007, when I heard about a shelter for deported children in the city of Mexicali, state capital of Baja. During a research trip there, I was encouraged to contact a local reporter. On the appointed day, I met Sergio Haro at a Starbucks on the Mexican side of the border. What was supposed to be a short meeting turned into a three-hour conversation.

From that first meeting forward, I understood that all of the narrative threads I had been chasing — immigration, corruption and the rise of narco power in Mexico — converged in Sergio’s story. Through hundreds of dispatches and photographs, Sergio has borne witness to his native Mexicali and the surrounding border region for nearly three decades. His work is a kaleidoscopic record of place. It is also a testament to his dogged commitment to “the job.”

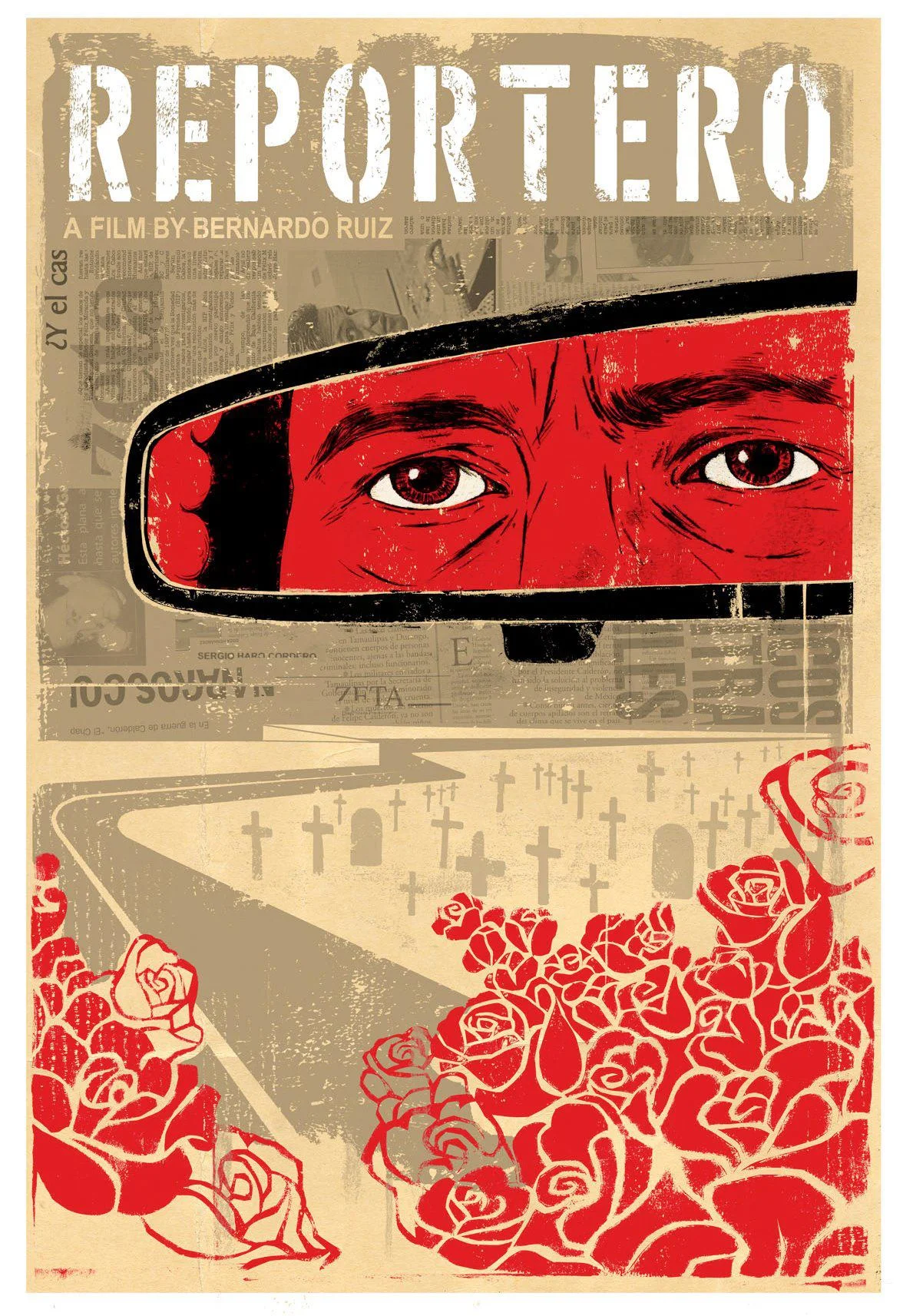

Most reporters don’t like to be the story, and Sergio was understandably reticent about being on camera at first. So, we began a series of conversations that initially didn’t have a clear objective. Instead, they were exploratory. Over the course of two years, I interviewed him dozens and dozens of times. Off-camera in the beginning. Sometimes just recording audio. Sometimes in the dark of his living room in Mexicali, waiting for the intense heat of the city to dissipate. Those conversations are the basis for Reportero.

The film is Sergio’s story, but it is also the story of his colleagues and the weekly newspaper Zeta (no relation to the cartel of the same name), where he has spent most of his career. Sergio is not the only reportero in the film. Jesus Blancornelas, founder of Zeta, who survived an attack by 10 hired killers is also the reportero. The murdered columnist and co-founder of the paper, Héctor Félix Miranda, is also the reportero. Sergio’s friend and collaborator, Benjamín Flores, gunned down just days after his 29th birthday, is the reportero. Adela Navarro, Sergio’s boss and the outspoken and driven co-director of the paper, is the reportera.

I see this film as part “character” story and part meditation on the nature of the job — a job that is difficult and often deadly. The Committee to Protect Journalists tells us that more than 50 journalists have been slain or have vanished in Mexico since December 2006, when President Felipe Calderón came to power and launched a government offensive against the country’s powerful drug cartels and organized crime groups.

What does it mean to report on the activities of organized crime or corrupt politicians in this context? What goes through a reporter’s mind when he or she is about to break a story that is, as Sergio says in the film, “like a grenade before you remove the pin”? Why persist when the risks are many, the benefits few? Reportero poses the same question that serves as the title of the collection of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya’s final dispatches before she was murdered in 2006: Is journalism worth dying for?

For me, Reportero is an act of remembrance. It is a wake for Sergio’s colleagues who have paid for their work with their blood. It is also an act of translation — but translation where fragments and testimonies from one place are granted a new life, in an entirely new and different place. The film is an act of celebration, for Sergio Haro and his many colleagues, who stubbornly persist.